Nuclear-Powered Pacemakers

In the mid 20th century, a promising new power source for pacemakers emerged: plutonium-238.

Plutonium is a radioactive material, which meant it could be used in extremely small quantities to create nuclear-powered pacemakers. Since lithium-ion batteries weren't commercially available yet, we had to get creative with our power sources.

By the time the first plutonium-powered pacemaker was implanted in a human in 1970, we knew enough about radiation to understand its dangers and how much exposure was safe. This new generation of devices had no long-term, ill effects on its hosts.

But even though it might technically be safe to walk around with trace amounts of plutonium powering your heart, this is still a terrible idea, and there are two groups that really, really hated it.

The first is the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which likes to keep track of where radioactive material is stored. Surgically implanting plutonium inside of people before sending them back out into the world makes that difficult.

And the second group that hated nuclear-powered pacemakers?

The crematorium industry.

You see, when you heat a pacemaker up to 1,500° fahrenheit, it has a nasty tendency to explode, causing non-trivial damage.

This phenomenon — pacemaker explosions in crematoria — is actually not exclusive to plutonium-powered pacemakers, since batteries behave similarly at extreme temperatures. In fact, as recently as 2002, researchers Christopher P. Gale and Graham P. Mulley found that roughly half of the UK's crematoria have experienced pacemaker explosions. They write in their paper's abstract:

We found [. . .] that pacemaker explosions may cause structural damage and injury and that most crematoria staff are unaware of the explosive potential of implantable cardiac defibrillators.

You might be wondering, "how is this possible?" Surely there must be a process in place for preventing this kind of thing from happening. And you'd be correct. Gale and Mulley have an answer:

Crematoria staff rely on the accurate completion of cremation forms, and doctors who sign cremation forms have a legal obligation to provide such information.

Of course, even doctors make mistakes sometimes, and things slip through the cracks.

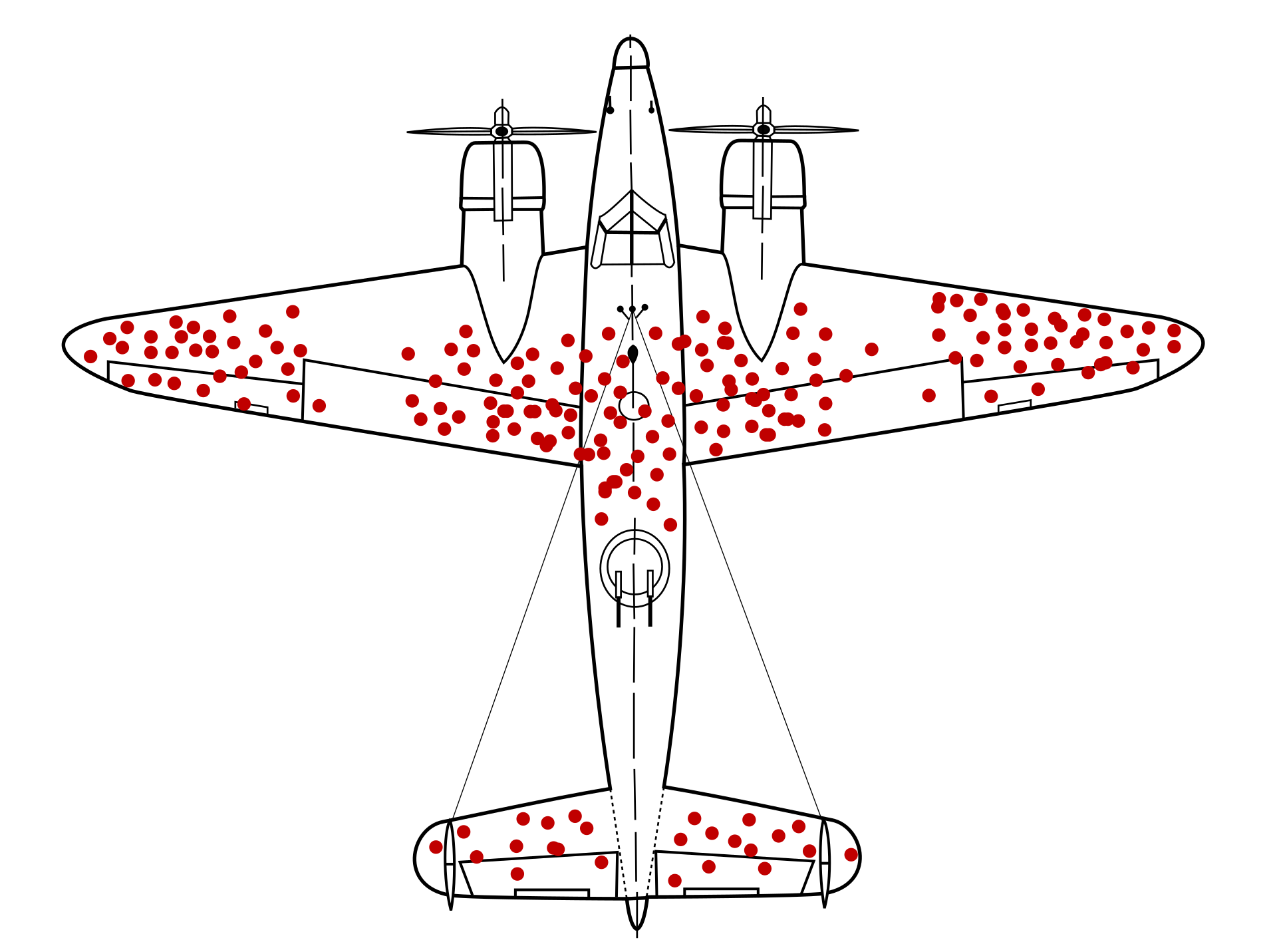

Most of us are fortunate to not have to make life or death decisions in our work. You may not be in a position where a wrong decision leads to serious injury, but when creating something new or changing an existing process, it's still worth asking: What could go wrong? And when something does go wrong, despite your preventative measures, how do you plan for that?

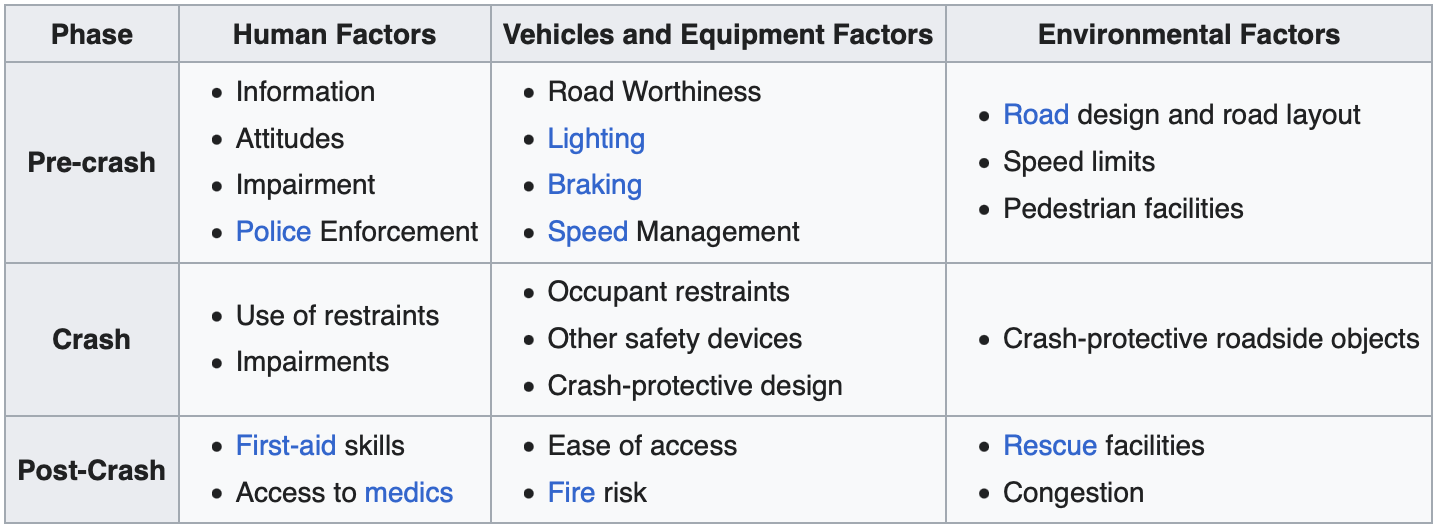

Coincidentally, the same year doctors implanted the first nuclear pacemaker in a human, William Haddon created the Haddon Matrix, the most commonly used framework in the injury prevention field for evaluating risk factors before, during, and after an incident.

Here's an example Haddon matrix from Wikipedia:

Such a formal risk evaluation might be overkill most of the time, but it's a useful reminder that every decision we make has second-order effects.

When we acknowledge that the world is messy and anticipate that multiple things can — and will — go wrong, we can design around and plan for those events.

And please, whatever you do, don't put plutonium inside of people.

P.S. Here's an image of Brunhilde, the world's first nuclear-powered dog (he received a plutonium pacemaker in 1969). Clearly a good doggo, despite being slightly more radioactive than most pups.